서론

골다공증은 골량의 감소와 미세구조의 이상을 특징으로 하는 대사성 골 질환으로 뼈가 약해져 쉽게 부러지는 상태의 질병으로[1], 임상에서 골다공증을 진단하는 데 널리 사용되는 골밀도(Bone Mineral Density, BMD) 측정은 일반적으로 골절 위험의 대용으로 사용된다(2). 이러한 특징의 골다공증 진단에 사용되고 있는 이중 에너지 X선 흡수법(Dual-energy X-ray Absorptiometry, DXA)은 허용 가능한 정밀도 오차, 우수한 정밀도 및 재현성으로 BMD를 측정하는 기준 방법이다[3]. 하지만 DXA 검사의 오류는 영상의 획득 및 결과분석에서 일반적으로 보고된 것처럼 자주 발생한다[4-11]. 따라서 다른 많은 진단 검사와 마찬가지로 DXA 스캔은 BMD 측정에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 이상 여부를 해석하는 의사와 방사선사가 비판적으로 평가해야 한다[3]. 골밀도 영상 보고의 오류는 1% 미만에서 30% 이상까지 다양한 비율로 잘 알려져 있다[12-14]. 이는 임상에서 BMD 결과에 영향을 미칠 수 있는 다양한 인공물 및 질병 과정에서 발생하는 다양한 문제인식은 DXA 스캔의 최적 해석에서 매우 중요할 수 있다[15]. 최근 연구는 국제임상골밀도학회(International Society for Clinical Densitometry, ISCD)의 약 6,000명의 회원을 대상으로 DXA 보고서의 품질에 대한 인식을 조사했습니다[6]. 조사를 받은 임상의의 21% (3,488명 중 743명)와 기술자의 32% (2,362명 중 754명), 대부분의 임상의(71%)와 수많은 방사선사(45%)가 잘못된 DXA 해석을 한 달에 한 번 이상 보고 있다고 보고했다. 거의 모든 임상의(98%)가 질이 낮은 DXA 보고서는 환자 관리에 유해하다고 느꼈으며, 또한 DXA 스캔 전에 인구통계 정보(연령, 성별 등)가 잘못 입력되었기 때문에 오해를 초래하는 보고서나 부정확한 보고서가 생성될 수 있음이 발견되었다. 따라서 방사선사가 골밀도 검사를 수행함에 있어 기본적으로 알아야 할 오류 문제를 인식하고 결과에 따라 발생할 수 있는 잘못된 진단과 치료를 방지하고, 그에 따라 발생하는 불필요한 비용을 줄이기 위함을 목적으로 한다.

본론

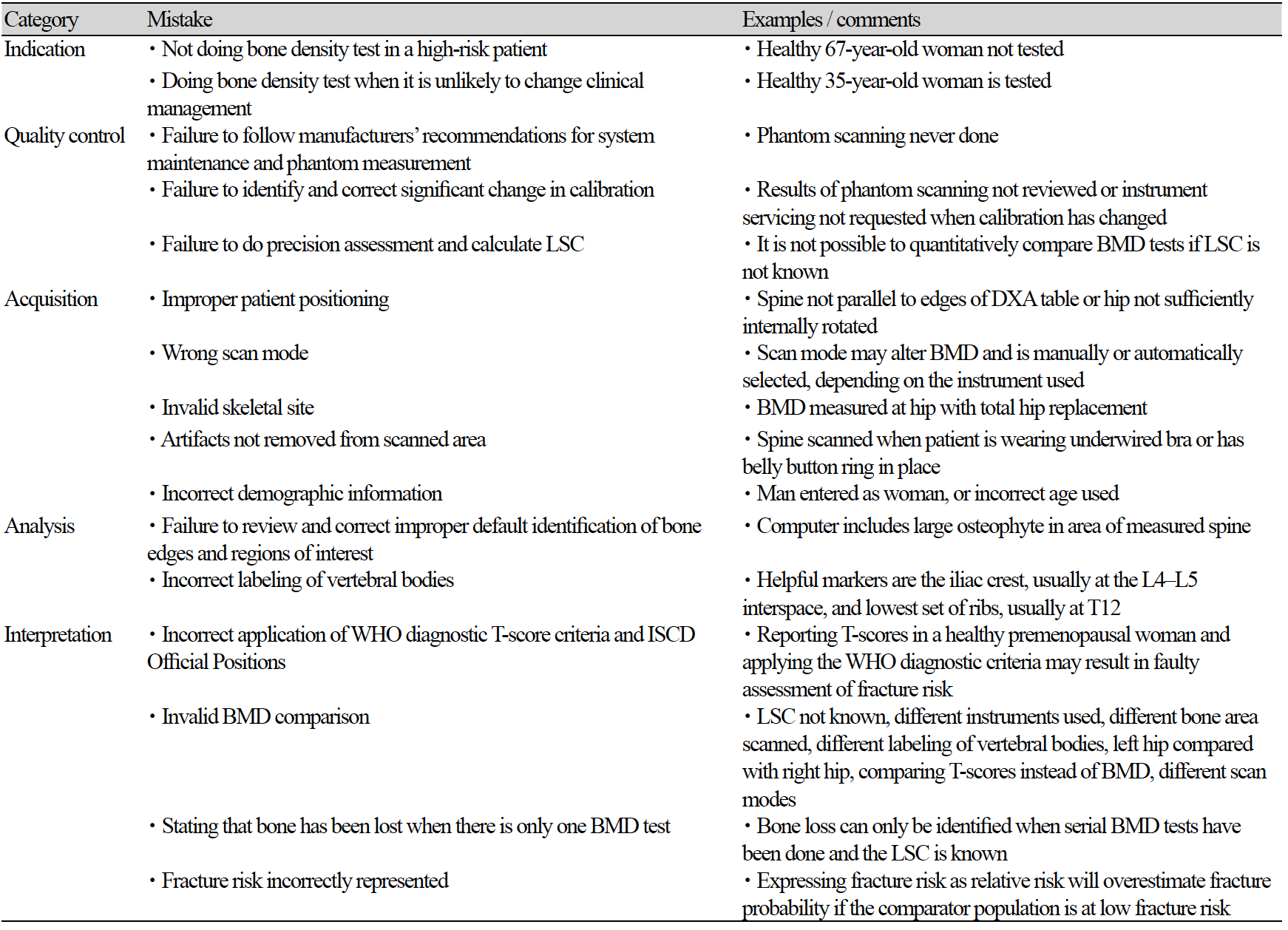

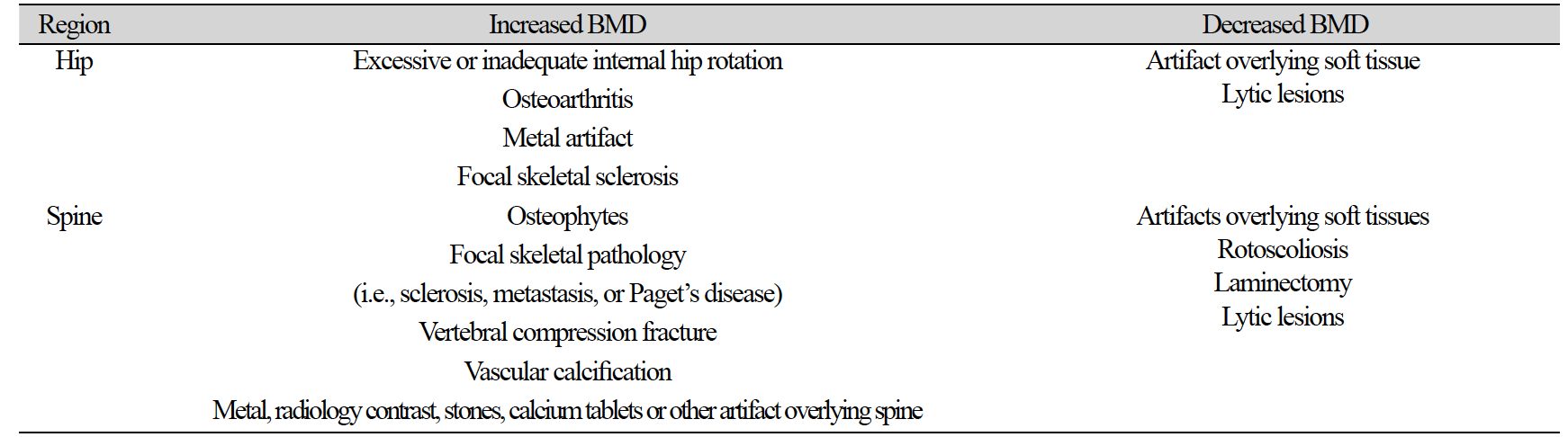

DXA 골밀도 검사 오류의 주요 원인은 운영자의 관리 하에 있다[15, 16]. 고품질 DXA 보고서를 생성하려면 장비 교정 변경, 부적절한 환자 위치 결정 또는 분석, 교락 아티팩트 인식, T 및 Z 점수 계산을 위한 참조 데이터베이스의 올바른 선택 등 오류 잠재력 원인을 이해해야 한다[9]. 아래의 도표(Table. 1)는 흔히 발생하는 골밀도 검사의 실수를 나타낸 것이다[17]. 따라서 아래의 내용을 기준으로 방사선사의 검사 및 결과분석에 대한 기술적 요인으로 발생할 수 있는 오류의 원인을 분석하고 대처방안을 기술하려 한다.

1. 검사 전 확인

1. 1. 나이, 성별, 인종, 체중

골밀도 검사 후 진단에서 가장 기본적으로 확인해야 하는 것은 환자의 정확한 신원 정보이다. 또한 인구통계에는 환자의 이름, 생년월일, 성별, 병원등록번호 또는 기타 식별자, 신장, 체중, 스캔일, 보고일, 추천 의사의 이름, 판독의의 이름 및 BMD 시설의 이름과 위치를 포함해야 한다[6, 18-21]. 체중과 키는 BMD 시설에서 측정해야 한다[22, 23]. 측정을 수행할 수 없는 예외적인 상황(예: 환자가 서있을 수 없는 경우)을 제외하고는 환자가 보고한 값이나 다른 의료 종사자가 제공한 측정치를 사용하지 말아야 하며 키 또는 체중 데이터가 BMD 시설에서 직접 측정되지 않은 경우는 보고서에 표시해야 한다[24]. 골무기질(Bone Mineral Content, BMC), BMD 및 골 면적의 측정치는 조직 구성의 영향을 받는다[25]. Laskey 등은 전신 스캔 모드와 척추 스캔 모드의 BMC, 골 면적 및 BMD 결과를 비교하여 전신 스캔 모드가 10 ㎝ 이상의 깊이에서 BMC 및 골 면적의 값이 높게 나타났으며, 깊이 또〮〮는 두께가 감소하면 BMD가 증가했다, 다만 팬텀과 물을 이용하여 연구가 진행되어 실제 생체 내 상황과는 다를 수 있지만 비만인 경우 BMD 정확도가 떨어질 수 있다고 보고하였다[26]. 그리고 Svendsen 등은 Van Loan과 Mayclin [27]이 수행 한 것처럼 체중과 조성의 큰 변화가 DXA의 뼈 가장자리를 정확하게 감지하는 능력에 영향을 미치고 뼈의 면적 추정을 변경할 수 있다는 것을 제안했다. 또한 Gary R. Hunter et al. 의 연구에서는 적당한 체중은 BMD 손실과 관련이 없고, 저항 훈련 및/또는 점프 훈련과 같은 고강도 훈련은 유지 관리 또는 체중 감량 중 BMD 증가와 관련이 있고, 체중 감량 중 칼슘 및 비타민 D 섭취 유지는 BMD 유지와 관련이 있다고 보고하였다[28].

1. 2. 임신여부

임신의 경우 태아의 방사선 피폭의 우려로 검사가 불필요하다고 판단하는 사람들과의 법적인 소송을 피하기 위해서는 특별한 이유가 없는 경우를 제외하고는 검사를 진행하지 않는 것이 바람직하다. M Kaur et al.의 연구에서 피크 골량에 영향을 미치고 후속 삶에서 골다공증을 일으킬 위험에 영향을 줄 수 있는 일반적인 생리학적 사건으로, 46명의 정상 여성의 임신 전과 출산 직후 이중 에너지 X 선 흡수 방법에 의해 BMD를 측정하고, 임신 실패 30명의 대조 여성과 비교한 연구에서 임신한 여성과 임신하지 않은 여성 사이에는 차이가 없다고 보고하였다[29]. 그리고 단일 광자 흡수(Single Photon Absorptiometry, SPA) 및 이중 광자 흡수(Dual Photon Absorptiometry, DPA)에 의해 결정된 피질 또는 뼈의 골밀도에 유의한 변화는 보이지 않았다는 보고도 있다[30-33]. 하지만, Naylor et al.은 임신 중 피질 부위의 BMD 증가와 소주골 부위의 BMD 감소를 보고했고[34], 요추 BMD는 임신 중 3.3% 감소하는 것으로 보고되었다[35]. 따라서 임신의 경우 객관적인 임상자료 증거를 기준으로 태아의 피폭 우려에 대하여 검사 시기를 미루는 등의 조정으로 대처해야 한다.

2. 장비 관리

2. 1. Daily QC & Periodic QC

BMD 측정의 일관성을 유지하기 위해서는 BMD 측정의 QC (Quality Control)가 필수적이다[36-38]. DXA를 이용한 BMD 측정의 QC는 정밀도와 정밀도의 오차 범위를 최소화하기 위해 수행된다. 이를 위해 환자의 상태, 측정 장비 및 방사선사의 경험으로 인한 오차 범위는 품질 관리에 의해 최소화되어야 한다[39]. 따라서 ISCD에서 권고하는 내용에 부합하여 장비 정도관리와 검사자(방사선사) 정도관리가 기본적으로 수행되어야 한다.

3. 이물질 유무

골다공증 검사 시 나타날 수 있는 이물질의 유형은 제게 가능한 것과 그렇지 않은 것으로 구분할 수 있다. 액세서리는 검사 전 제거 할 수 있도록 접수 단계에서 설명하고, 그 외 수술에 의한 외과적 고정 장치나 검사를 위한 조영제 및 칼슘제제 약물복용 등에 관한 사항을 철저하게 스크리닝 해 주어야 한다. DXA를 사용한 최적의 골밀도 측정은 아티팩트를 최소화해야 한다[40]. 이들 중 대부분이 내부에 있으며 외과적 고정 장치, 골관절염, 석회화 된 대동맥 또는 임플란트 등을 제거 할 수 없다[41-47]. 또한 위장관에서 제거되지 않은 바륨과 테크네튬은 DXA 측정 결과에 악영향을 미친다[24, 48]. 칼슘 정제 섭취도 유사한 영향을 미치므로 척추 DXA 결과에 혼란을 줄 것이라고 추정된다. 칼슘 정제는 피할 수 있는 아티팩트일 수 있으므로 많은 DXA 센터와 ACR (American College of Radiology) / RSNA (Radiological Society of North America)는 일상적으로 스캔 수행 24시간 전에 칼슘 정제를 섭취하지 말라고 조언한다[49]. 흥미롭게도, DXA 스캐닝 전에 칼슘 정제를 피하라는 이러한 권장 사항은 다른 약물이나 보충제로 확장되지 않으며 추상적 형태로 제시된 생체 외 데이터 결과는 많은 정제가 팬텀 BMD 측정을 변경할 수 있음을 시사한다[50].

4. 골밀도 검사

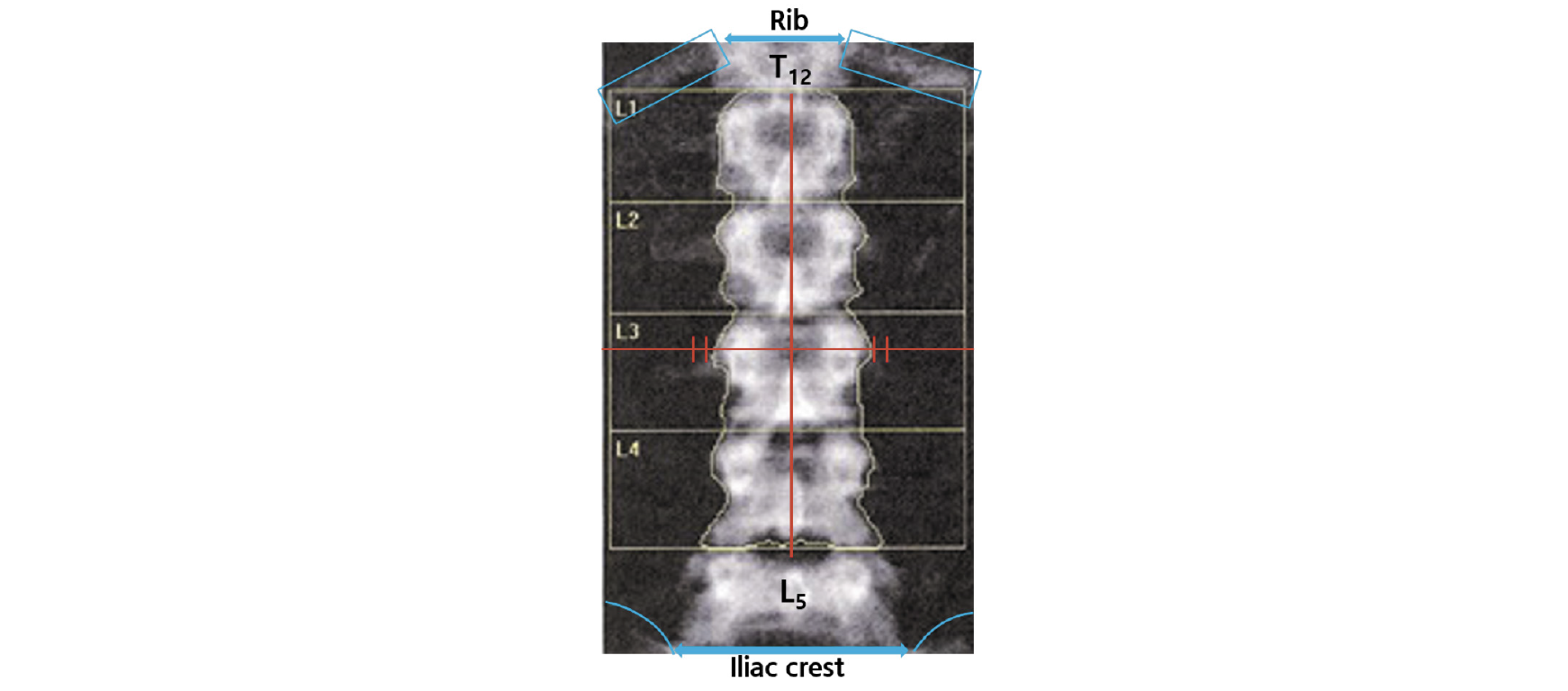

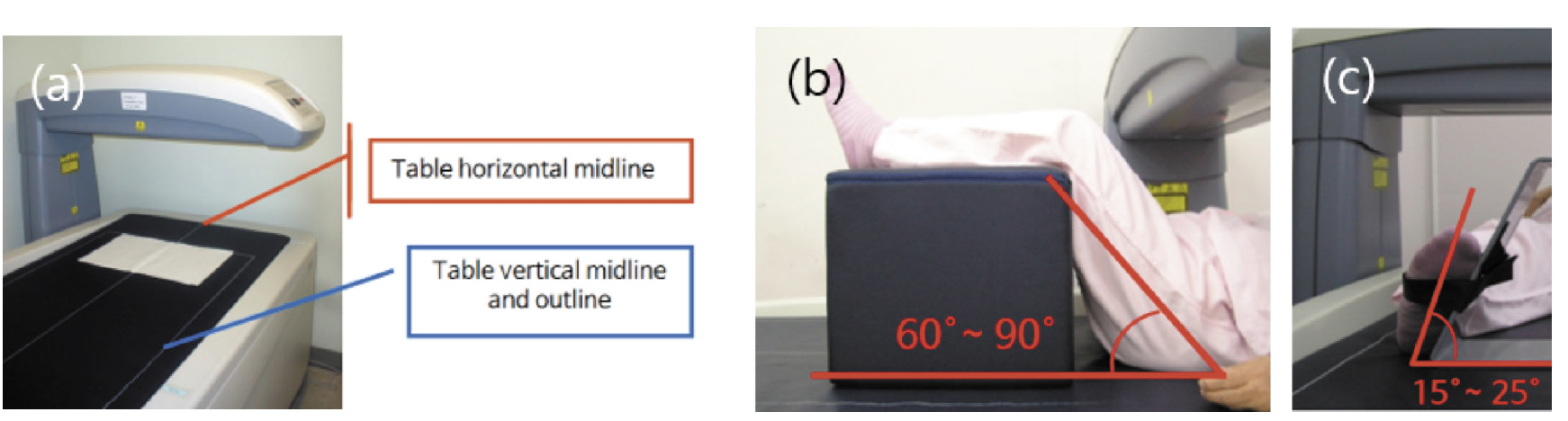

올바른 검사를 위해 가장 기본은 환자의 올바른 자세 잡이다. 자세 잡이를 일관적으로 유지하기 위해 요추 검사 시 검사 테이블에 그려져 있는 중앙선과 외곽선을 이용하여(Fig. 1-A) 편안한 상태로 가운데에 눕게 하고 힘을 뺀 상태에서 척추에 무리가 가지 않도록 다리를 아래쪽으로 살짝 당기고, 포지션 블럭을 이용하여 60°-90° 정도로 다리를 구부려 올려 굴곡이 되어 있는 척추를 펴서 자세를 유지하여 움직임이 없도록 하고(Fig. 1-B), 대퇴부 검사에서는 다리에 힘을 뺀 상태에서 15°-25° 내 회전을 시키고 대퇴골의 경부 축이 스캔 테이블의 평면과 평행이 되도록 위치하는 것이 중요하다(Fig. 1-C). 다만 여러 사람이 근무하는 경우 항상 똑같은 방법으로 환자 자세를 유지하는 것이 방사선사 간 정밀도 오차를 줄이는데 도움이 될 것이다. 또한 검사는 제조업체 프로토콜 준수하고, 적절한 위치 지정 및 하위 영역 할당, 뼈 추적, 관심 영역 결정 및 품질 보증을 포함하여 스캐닝 수행 방법의 모든 기술적 측면에서 주의를 기울여야 한다[6, 51-62].

Fig. 1. The center line and outline of the examination table to maintain a consistent patient posture in bone mineral densitometry (a). During the lumbar examination, have the patient lie down in the middle in a comfortable state, and pull the legs slightly downward to avoid straining the spine in a relaxed state. Then, using the position block, bend your legs up to 60°-90° to maintain the posture by straightening the curved spine (b). In the femoral examination, the leg is rotated within 15°-25° with the leg relaxed, and the cervical axis of the femur is positioned so that it is parallel to the plane of the scan table (c).

4. 1. Spine

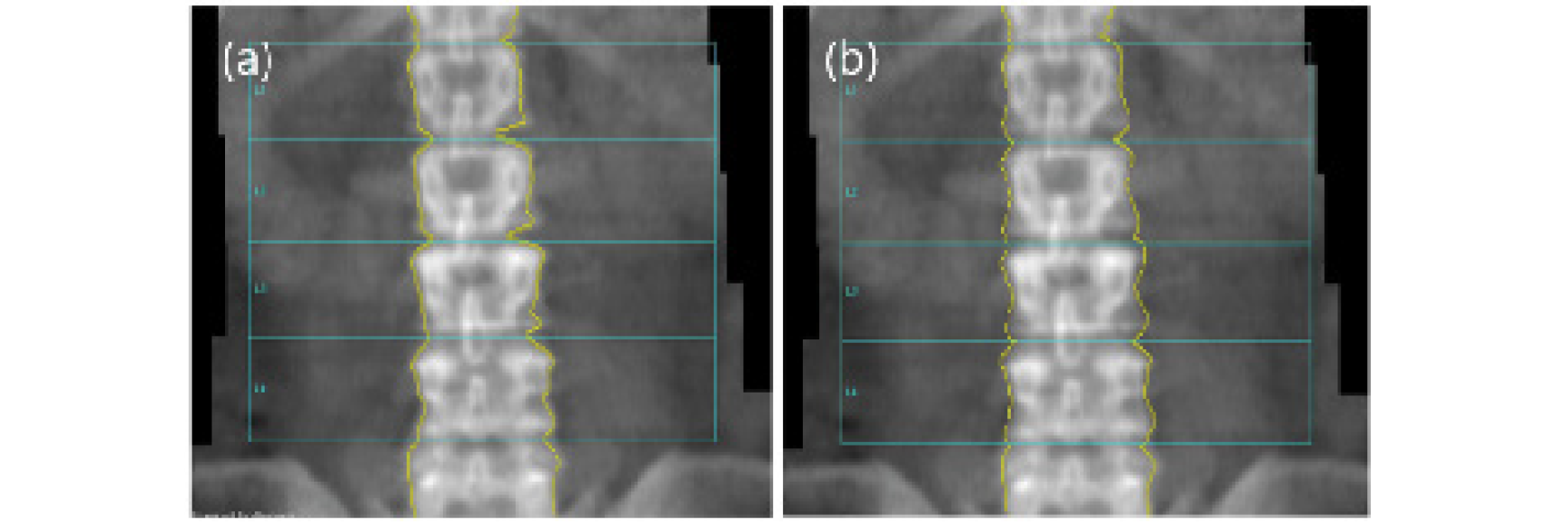

L1-L4 BMD 평가에서 극돌기는 곧은 정중선의 중심에 있어야 하며 천골(장골)의 일부와 갈비뼈가 있는 척추의 일부(일반적으로 T12)를 포함해야 하며, 척추의 회전이 없어야 한다. 만약 정중선을 기준으로 방향에 상관없이 60°까지는 BMD가 거의 20% 가까이 감소한다[63]. 이는 BMD가 영역별 BMC로 평가되기 때문이다. 따라서 척추 측만증 환자의 경우 정확한 골밀도 측정이 어려울 수 있다. 그리고 척추의 형태학적인 식별은 천골부터 번호가 매겨져야 6개의 요추 또는 변동성이 있는 12번 늑골로 인한 잘못된 척추 식별 오류를 방지할 수 있다. 그리고 L1은 U자형, L2는 V자형, L3은 Y자형, L4는 H자형이고 L5는 대문자 I가 옆으로 누운 형태로 나타난다(Fig. 2). 또한 측면 보기에서 12번째 늑골은 L1과 겹치고 골반은 L4와 겹치므로 라벨링이 어려울 경우 요추를 식별하는 데 도움이 될 수 있다[64].

4. 2. Femur

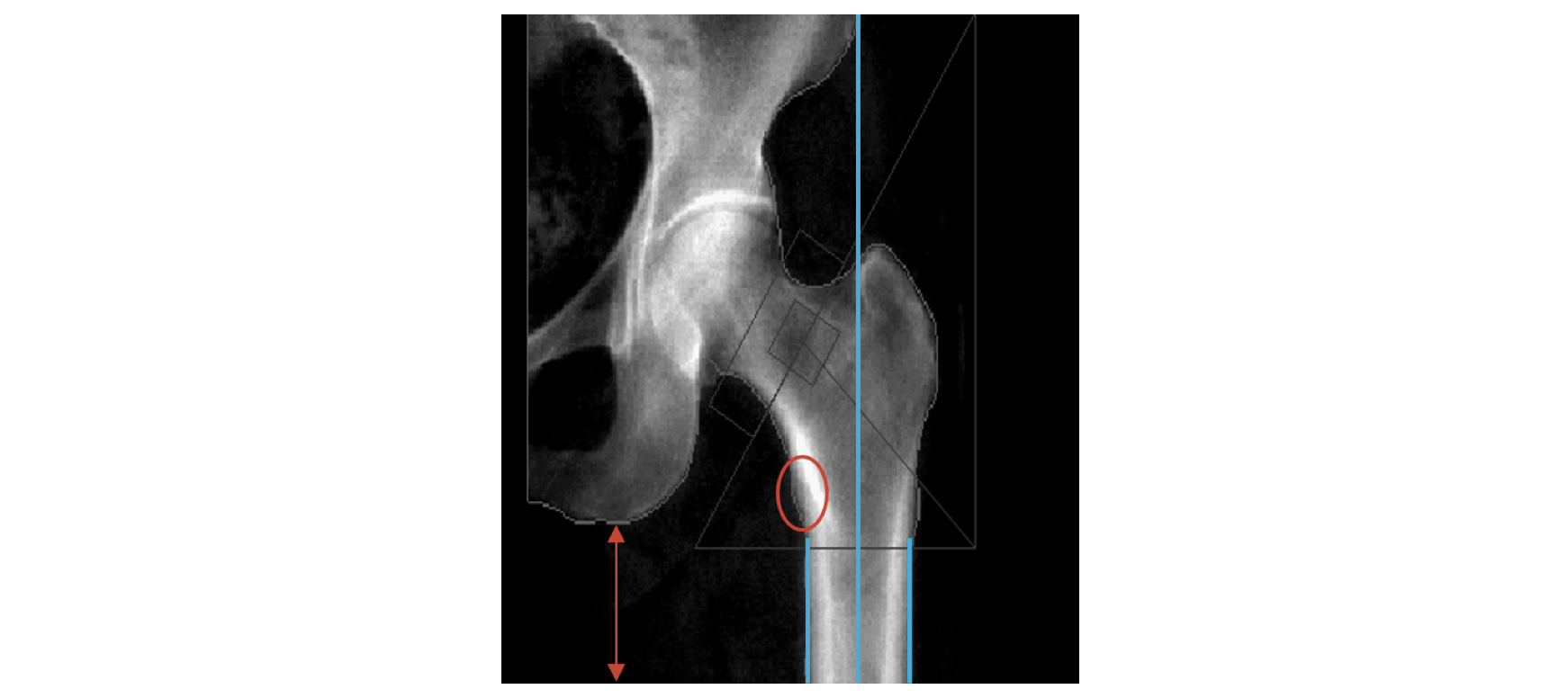

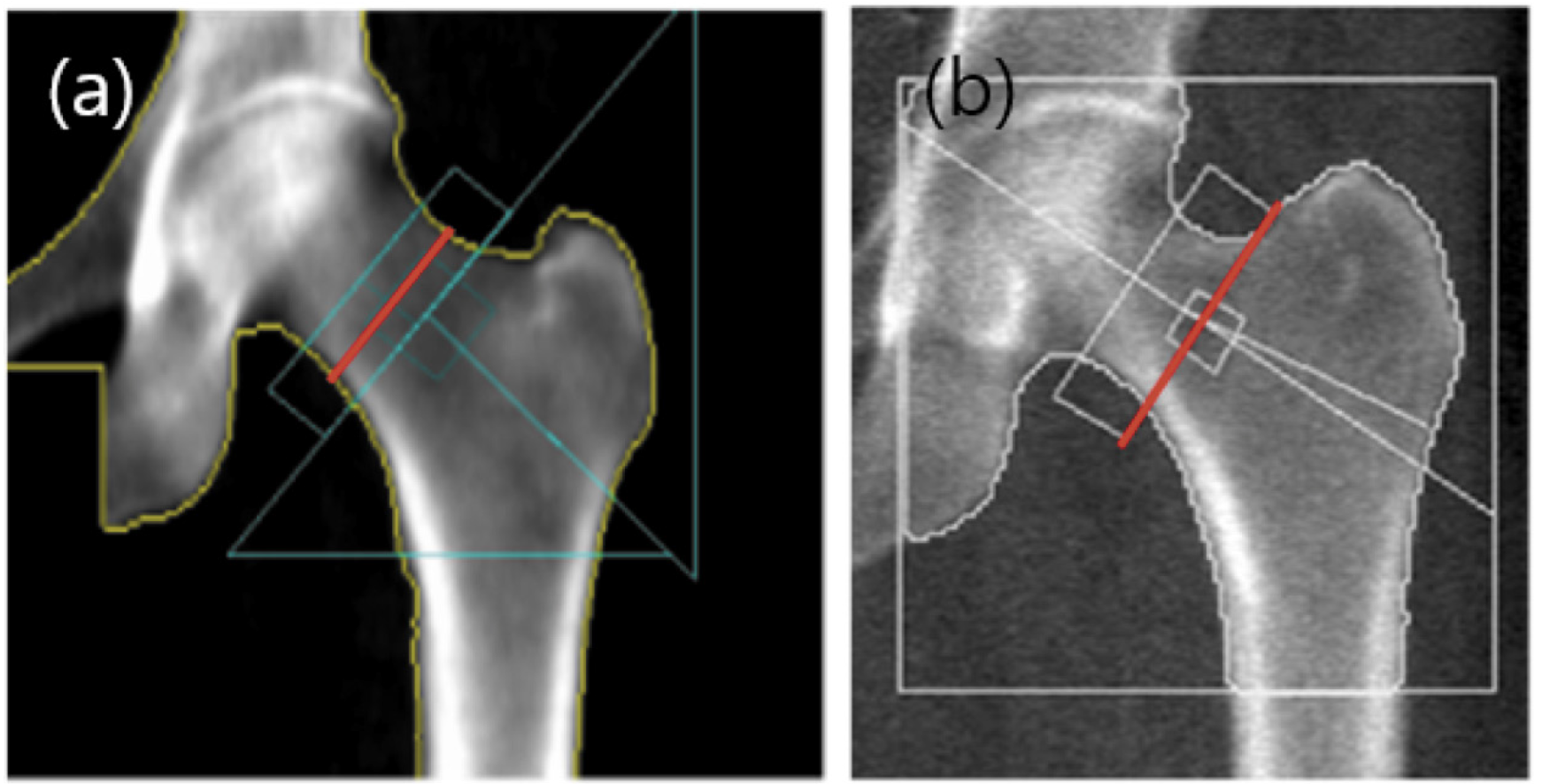

대퇴골 경부의 BMD 평가에서 해부학적인 자세는 소전자가 살짝 보일 정도의 자세이다. 샤프트는 일직선의 되어야 하고 소프트 티슈가 충분하게 포함되어야 한다(Fig. 3). 만약 소전자가 보이지 않는 경우는 골밀도가 증가하는 경향을 보인다. Femoral neck box는 GE lunar와 Hologic의 분석에서 차이가 있다. GE lunar의 경우는 대퇴골두와 전자의 중간 지점인 가장 좁은 부분에 위치하며(Fig. 4-A), Hologic의 경우는 대퇴골 경부의 가장 말단부에 위치한다(Fig 4-B)[65]. 근위 대퇴골의 경우 왼쪽을 측정할 수 없거나 유효하지 않은 경우 또는 이전에 오른쪽 엉덩이를 측정한 적이 있는 경우가 아니면 왼쪽을 측정해야 한다[66, 67].

5. 결과분석

최소 2개의 골격 부위를 스캔하고 보고해야 한다[18, 51, 58, 68-71]. 그리고 유효한 스캔이 있는 각 골격 부위에 대해 보고된 골밀도 결과는 절대 BMD (g/㎠에서 소수점 이하 3자리까지) 및 T-점수(소수점 1자리까지)가 포함되어야 한다[18, 51, 71, 73].

5. 1. Spine

요추의 경우 보고서에 결과의 그래픽 표현이 포함된 경우 그래프에는 해석에 실제로 사용된 척추에 대한 데이터 및 참조 곡선이 표시되어야 한다[18]. 해당 척추의 T-점수가 다음으로 높은 값을 갖는 척추의 T-점수보다 1 표준 편차 이상 큰 경우 특정 척추를 제외하는 것을 고려할 수 있다[18, 51, 74]. 밀도가 높은 척추뼈를 반드시 배제해야 하는 것은 아니지만, 인공물의 원인을 평가하고 척추 분석에서 포함 여부를 결정해야 한다.

5. 2. Femur

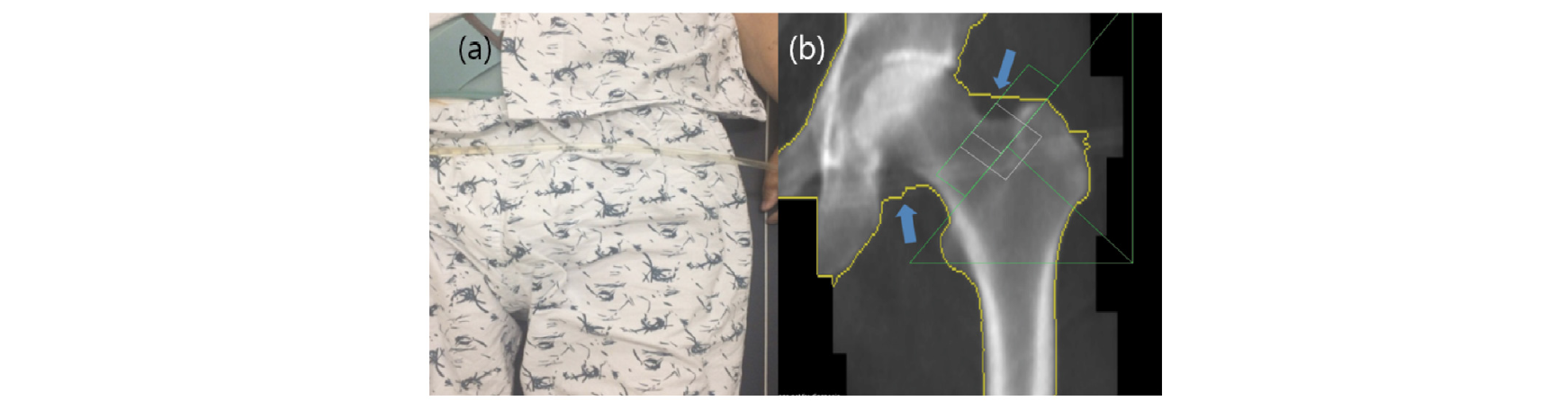

근위대퇴골의 경우 전체 고관절, 대퇴골 경부 및 전자 영역에 대한 결과를 보고해야 한다[73-77]. 검사가 종료된 후 반드시 영상을 확인하고 air scan이 있는지의 여부를 살피는 것 또한 중요하다(Fig. 4). 만약 아래와 같은 영상이 확인되면 마른 체형인지를 확인하고 적정위치에서 검사가 이루어졌는지 확인하고 rice bag이나 스캔모드를 변경해서 재검사를 진행하고 재검사시 동일한 조건으로 검사를 수행할 수 있도록 메모를 해두어야 한다.

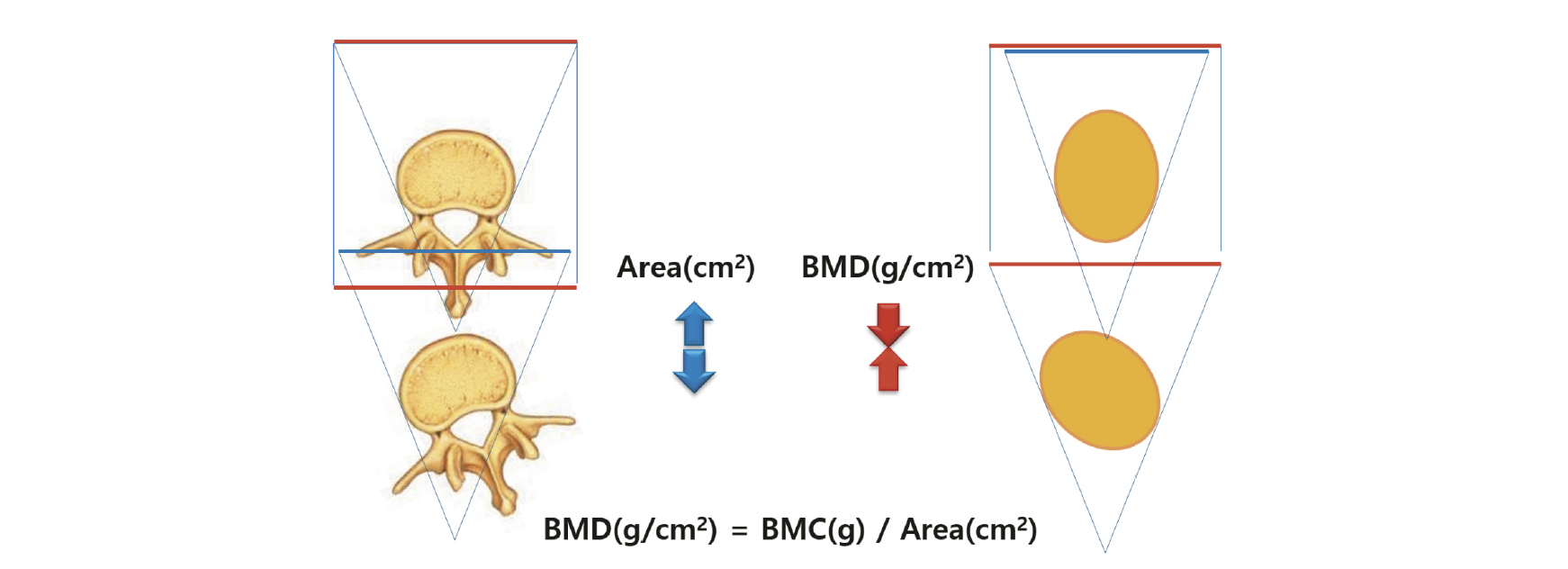

또한 원위 대퇴골 검사는 대퇴골의 회전에 따라 골 면적에 차이가 발생하여 결과분석에 영향이 있다. 즉 골면적이 증가하면 골밀도가 감소하고, 골면적이 감소하면 골밀도가 증가한다. 따라서 골밀도 검사 시설에서는 분석 시 각 장비회사의 프로토콜에 따라 자동분석과 수동 분석을 적절하게 병행하는 것이 검사의 정확도 측면에서 유리하다. 특히 재검의 경우는 ROI (Region of Interest) Copy 기능을 이용하여 이전 검사와의 동일한 영역으로 일관되게 비교 분석하는 것이 바람직하다(Fig. 7).

Fig. 7. This picture shows the difference between automatic analysis and manual analysis. If the edge of a bone cannot be recognized, a difference in BMD occurs when the edge is mapped according to the standards recommended by each manufacturer (a; auto mapping, L1~L4: BMD=0.857, T-Score=-2.4, b; manual mapping, L1~L4: BMD=0.788, T-Score=-2.7).

5. 3. 질병, 퇴행성 변화, 공간점유병소 등

검사하는 부위의 구조적인 이상이나 인공물 등은 결과에 상당한 영향을 미칠 수 있다. 체중과 같이 BMD 결과를 감소시키거나 증가시킬 수 있는 BMD와는 독립적인 요인이 있다(Table 2)[19].

검사 전 이물질 제거가 되지 않은 경우는 ROI 설정에 오류가 발견되거나 분석에 영향이 있으므로 반드시 검사 영역에 포함 시켜서는 안 된다(Fig. 8).

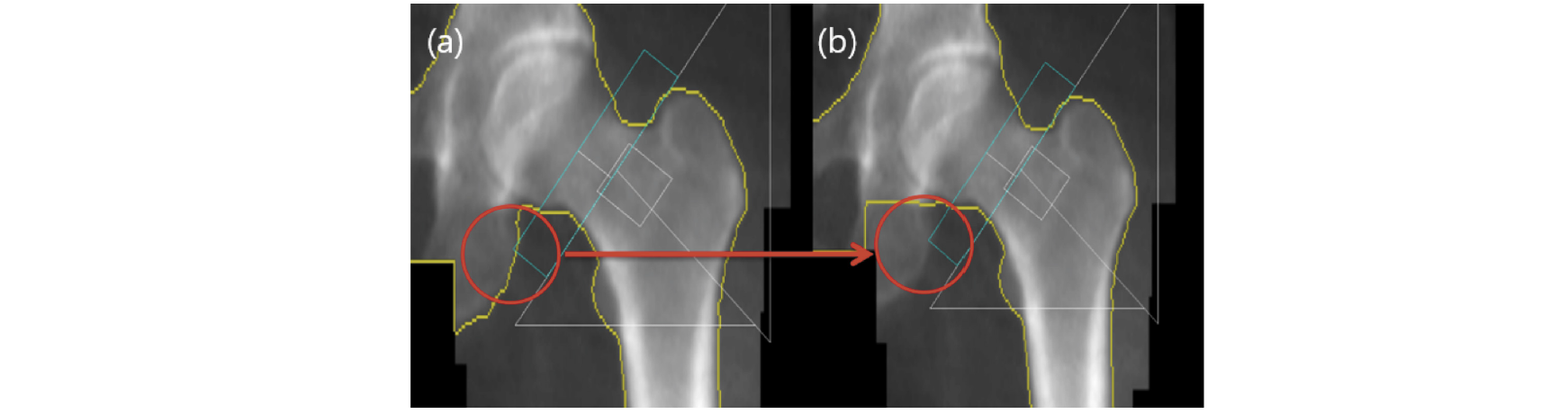

그리고 원위 대퇴골 검사의 경우는 Femur Neck 분석에서 ROI Box영역이 좌골과 겹치는 경우가 발생하는데 이에 따라 골밀도의 차이가 발생할 수 있기 때문에 주의해야 한다(Fig. 9).

Fig. 9. In the analysis of Femur test results, if Ischium overlaps in the neck ROI box, a difference in BMD occurs. Therefore, the overlapping part must be removed by manual mapping (a; Ischium is overlapped with Femur neck ROI box (neck BMD: 1.111 g/cm2, Total: 1.166 g/cm2, b; Ischium removed from Femur neck ROI box (neck BMD: 1.136 g/cm2, Total: 1.189 g/cm2). The neck increased by 2.2% and the total increased by 2.0%.

결론

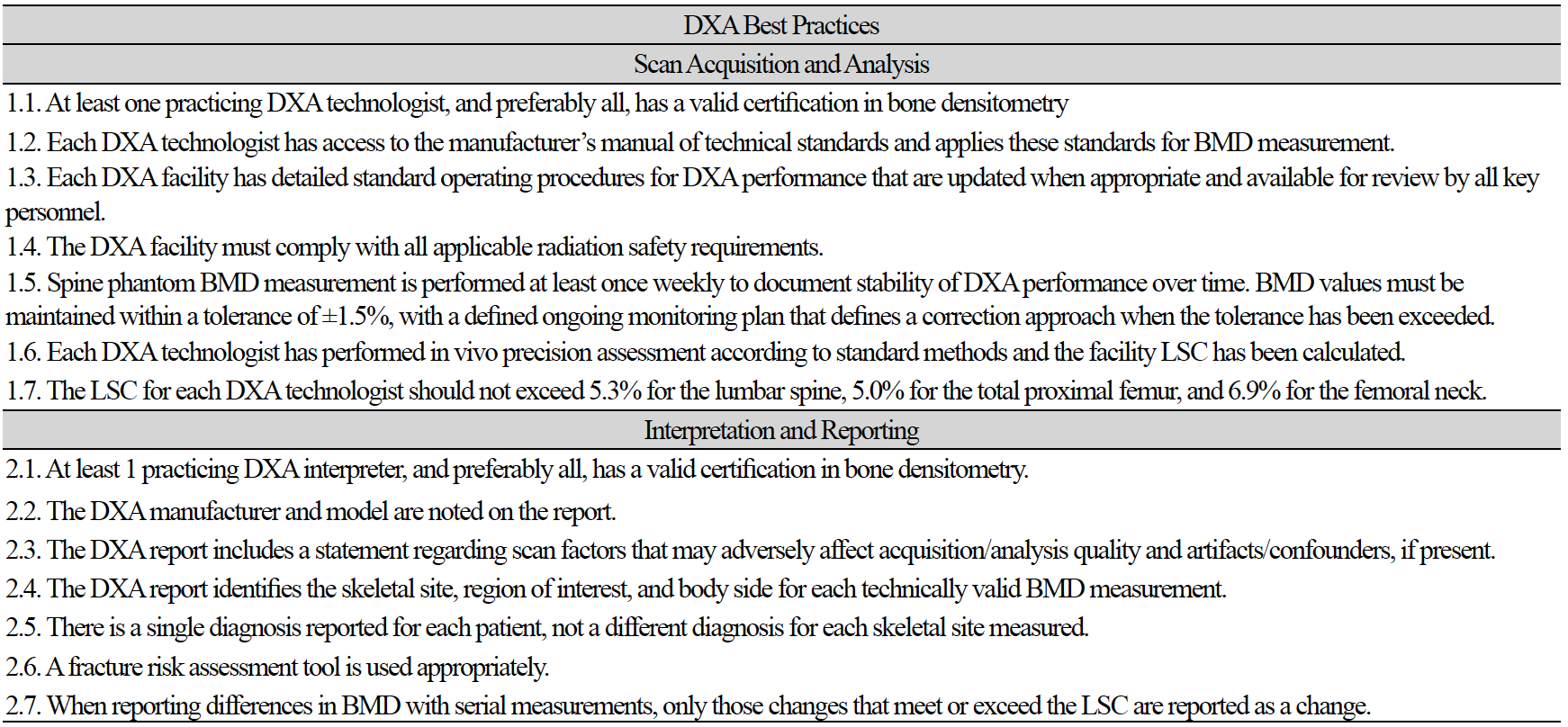

골밀도 검사의 경우 여러 가지의 영향으로 인하여 오류 발생 가능성이 많다는 것은 본문에서 나열된 많은 연구를 통해 알 수 있다. 정확한 검사를 위해 가장 중요한 역할을 하는 방사선사는 오류 가능성에 대하여 미리 인식하고 있는 것이 중요하며, 검사마다의 오류 가능성에 대하여 준비 대처할 수 있는 능력을 키우는 것이 필요하다. 그러기 위해서는 정기적인 교육이 필수적이 요소라고 생각된다. 아래의 도표(Table 3)는 DXA 판독의사, 방사선사의 가이드 및 기대치를 제공하기 위한 것으로[9], 이러한 DXA 모범 사례를 준수하여 방사선사의 검사 및 결과분석에 대한 기술적 요인으로 발생할 수 있는 오류의 원인을 분석하고 대처하기 위한 기본적인 사항으로 각 병원에 특성에 맞게 적용하면 도움이 될 것으로 기대된다.